Most of us idealize and romanticize France – and rightly so. It has an endearing culture rich with history, the arts, cuisine, wine, beautiful countryside no matter what region, all operating on the legacy of the French Revolution: Liberty, Equality and Fraternity. Yet, there have been brutal moments in French history where the forces of good and evil met creating great suffering.

In the 13th century there was the Inquisition, the result of perceived heresy among the Cathars. Then in the 16th century France saw the War of Religions, Protestant vs. Catholic. In 1789, given the abuses of royalty, the bourgeoisie, the Catholic Church and lingering feudal practices, the French Revolution was the result creating another tumultuous period. Later In 1871 there was the Paris Commune, one more battle of rich vs. poor. Since then, there have been continued struggles defining exactly what Liberté, Egalité & Fraternité actually mean to French society.

Following the French Revolution, there have been thus far five “French Republics,” all with different priorities. In the 1930s, the Third Republic was at risk of being overthrown.

I’ve briefly written about my friend Gayle Brunelle’s book Murder in the Metro (Louisiana State University Press, 2010) co-authored with Annette Finley-Croswhite). You can find the post here.

Murder in the Metro was about the Cagoule, as they came to be known, and their clandestine operations that came close to toppling the Third Republic. Had it not been for the Second World War, the demise of the Third Republic might have happened as a subversive internal event.

Cagoulards (members of the Cagoule) used means that have become familiar to us today in terms of manipulating the press: what we now call “fake news.” They also used obfuscation to confuse the masses denying their actions and, instead, blaming the government.

Given the events leading up to the surrender of France to the Germans in June, 1941, members of the Cagoule dispersed and chose sides depending largely upon perceived opportunity. Some collaborated directly with the Germans because they felt a Nazi regime, which respected the role of capitalism, would be better than the Bolshevik or communist philosophy where corporate profit-making was held in disdain. Following World War II, former Cagoule members moved on, again largely based on opportunism.

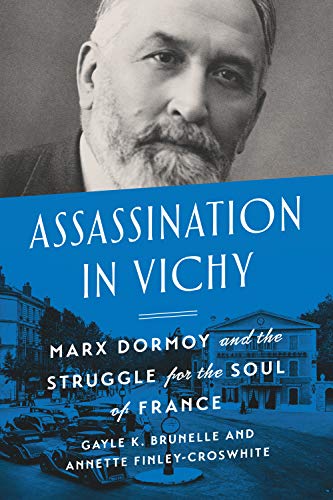

Marx Dormoy was Interior Minister of France in the 1930s under the government of Léon Blum. Dormoy led the investigation of the Cagoule and therefore became an enemy to anyone who had been a part of it. Once Maréchal Pétain, a World War I General and hero, set up the provisional Vichy government in 1940, Dormoy became a target for he had more information than anyone on their dirty work and reputations and careers – including that of a future President of France, Francois Mitterand – could suffer should this information become widely known. Dormoy was therefore assassinated in July 1941 and that is the story of the second book by authors Gayle Brunelle and Annette Finley-Croswhite entitled Assassination in Vichy (University of Toronto Press, 2020).

The organization became known as the Cagoule, named by the right-wing conservative press who tried to make the public believe no such anarchical organization existed. They alleged it was merely a figment of Marx Dormoy’s imagination. They featured cartoons of members in black hoods (cagoule means “hood” in French) ridiculing Marx Dormoy and French government and likening the Cagoule to the American Ku Klux Klan (KKK). Members became known as cagoulards. Although the hoods were fictionalized, the press further sought to deny the existence of any such organization with their “fake news.”

Marx Dormoy was assassinated while under house arrest, under the orders of the Vichy government in a very brutal manner with a bomb planted under his mattress. While the Vichy government was suspected, it is the authors’ tireless investigative research that has confirmed this.

The authors’ research led to rather significant discoveries. This period of time hasn’t been discussed much by French historians and political analysts because it remains a difficult period in French history and we are still too close to it. There was also shame and humiliation among the French at being so quickly defeated by the Germans. The French were largely unprepared for World War II as they hadn’t upgraded their army with the latest technology whereas the Germans had. It was all over within a few days.

Like Murder in the Metro, Assassination in Vichy is a well-documented detective story. The authors weren’t finished when they completed the first book because there was more to tell. Their subsequent detective work in the form of archival research was meticulous, revealing information heretofore undiscovered and definitely unappreciated in France.

I’ve recently finished this second book and found it as intriguing as the first. Last summer I had taken a tour in Carcassonne to learn more about the French Resistance in our region. That is summarized here. It piqued my interest and I wanted to learn more.

Obviously the French Resistance extended throughout the country. What this new book revealed is the intrigue and deception at the highest levels of government.

I decided, because I had further questions trying to wrap my arms around the Resistance, the Vichy government and French politics in general, that I would interview Gayle for this blog. We spent several hours over two days to answer my questions. It was another edifying learning experience. There is much to know.

TOM: This is an enormous scholarly work. Looking at your sources of information, you were kept busy for a very long time. How long did it take to write the book? How many visits to France? How much time was actually spent here doing research?

GAYLE: Thank you Tom! I love your blog and Annette and I are very glad you enjoyed our books enough to find them worth writing about!

To answer your question, it took about a decade. A big issue was that we were teaching fulltime. About 75% of the documents were in the Archives de Paris and therefore accessible via derogation (special permission) because they were classified. That also meant you couldn’t take photographs of them. So we spent six weeks every year in the archives madly typing. A lot of the other documents, after the reform of the law in 2006, made it possible to photograph some documents. Still a derogation had to be obtained and the Archives de Paris in particular still doesn’t allow readers to photograph the documents on the Dormoy assassination. Once permission is received, one sits in a small room, and because you can’t take photographs, you type.

Writing the book took time. I used my 2016 sabbatical of one semester with about two months spent in France and the rest of the time used to create a structured timeline from the beginning to the end. This enabled an understanding of the cause-and-effect connections. Developing this timeline ultimately took about six months. Then it was possible to give the book structure. The conceptualization was the hardest part. Even with a narrative in the timeline, we had to figure out what was key. And when dealing with history, you must look at cause and effect. What were the important factors leading to the choices of the various players?

The process began in 2010 and for six years, we did pure research. Then I began to overlap research with the conceptualization. Once completed, we worked on writing. A draft of the book was ready by 2018 but required heavy editing to eliminate wordiness, repetition, etc.

TOM: I can identify! Just to write a post for the blog can take me several days of writing, rewriting, editing down, proofing and eliminating repetition. It’s work!

GAYLE: Yes, it is!

Between 2018-2019 Annette and I would get together during the summer for 3-4 weeks with the goal of cutting 40,000 words. We had decided upon the structure and chapters, but needed to hone down the writing.

Once drafted, the book went out to readers whose task it was to read the manuscript a couple of times. Their job was to take the perspective of prospective readers and, since they are professional historians, assess the accuracy of the research. They then wrote evaluations and identified what needed fixing.

Next, the publisher advised how many words they would accept. After a revision, it went back to the readers for another review, then to copy editors who inserted their comments. With that, we edited the draft once again.

Once the publisher agreed on the new draft, it went to a review of the galleys which had been marked up by the production editor. We did more proofs to winnow down the number of errors, placement of the pictures, getting permission for the pictures, and finally, creating an index (which we hired out). It took a while! We were making changes right up to a few weeks before going to press.

TOM: Exhausting!

GAYLE: Yes. But the editor is your friend. Still, there were moments of exasperation.

Teaching online and part-time made it easier. Annette still teaches fulltime [at Old Dominion University] and has two kids. You just have to keep at it. If you’re going to write something of quality, you have to pay attention. You have to read it out loud (and more than once). You have content, clarity and cadence so that it flows. You have to be sure the reader understands what you are trying to say. Otherwise, they may be distracted. It can’t be clunky or stilted. Reading out loud is really the best way. It’s also what makes the difference between an academic book and something that will attract non-academics – even if they’re not consciously aware.

TOM: How about the actual writing?

GAYLE: Annette & I have different voices. My voice tends to dominate because I write a lot of the initial chapter drafts. Annette then edits me rigorously.

I prepared by taking writing courses in the 1990s. I learned how to think about structure, narrative and cadence. I tend to be fulsome and verbose. Annette is more clipped so the combination works for us. We would spend hours hashing things over. Fortunately, we are friends. Nonetheless, our two styles add a layer of difficulty in the writing. There are chapters that stick out being in Annette’s voice vs. my own – particularly in Murder in the Metro. You don’t want that.

TOM: I enjoyed reading both books very much. Your vocabulary is rich and impressive and I believe you have a great writing style. I didn’t pick up on two different voices but simply felt it flowed though I was continually amazed at the coordination of detail. There is a lot to both stories! I can see where your timeline would help to organize and provide clarity.

GAYLE: I’ve been talking in full sentences since the age of six months. Writing has always been important and enjoyable. I was also a voracious reader and that helps.

TOM: I agree. I was the same way reading every book in my grade school library by the 5th grade.

GAYLE: Part of the success is having a vocabulary that allows you to economize on the number of words.

I taught my students that one of the best inventions for writers are colored post-its. When reviewing and organizing your research, establish a color code for each chapter then tag the research as needed. For example, Chapter 2 is orange, Chapter 3 is blue. It helps to keep track.

Another trick is to footnote as you write. This saves a lot of time later. Then, organize what the day’s objective is, assemble the necessary materials for footnotes, and proceed.

TOM: What turned you on to history as a career?

GAYLE: I wanted to be a fiction writer first. I have a feeling I will drift to that after I complete a few history projects. But I began as an American historian. I wanted to look at connections within the Atlantic world among Africa, Europe, and indigenous people of the Americas and the Colonies. I changed to Early Modernist and in my doctoral program focused on 16th & 17th century Europe, and the North and South American colonies. I also studied economics and found I have a knack for that. My first book was on the economic & commercial history of Normandy.

TOM: As a historian whose main interests are 16th-17th century France, this was a huge diversion. Why did you pursue it? Was it fun? Exhausting? Tiresome? Were you glad when it was done?

GAYLE: It was a lot of fun. I saw the potential of a good story with people I came to care about. Annette had a strong sense of wanting justice to be done. Laetitia Toureaux [the subject of Murder in the Metro] is a flawed but intrepid heroine. We were interested in her story, what happened and why, as well as the story of the Cagoule. With Dormoy [the subject in Assassination in Vichy] it was quickly apparent that he was a heroic figure who has been neglected in French history.

Both the Cagoule and Dormoy were fascinating. If you’re going to write a book on history it has to resonate on some emotional level. They were interesting and we felt like it was a story we wanted to tell. It helped that neither of us are at high profile universities. It didn’t matter if our research diverged from our key interest areas. There was much less pressure to turning things out in our own fields raising the reputation of the university. They didn’t care.

Annette changed not just her teaching field, but her research field. Her next book will be on the Holocaust in France because it resonates more emotionally for her.

I was the only professor in Early Modern Europe at my university [California State Fullerton] and I therefore continued to teach in that field. But I was intrigued by the story. At this point of time in my life being semi-retired, if I am going to do research, it will have to be because I am interested in the story. It becomes a labor of love given the amount of work required to do the job. Historians have to have a curiosity about why things unfolded as they did. You have to have something of a detective in you. And that explains why most historians are big consumers of detective novels!

TOM: What was the biggest revelation in this book that you privately alluded to me at one point?

GAYLE: One was finding Dormoy’s letters, a draft to Pierre Laval, indicating that he was involved with the Cagoule. This hadn’t previously been established.

Another was the realization that Gabriel Jeantet [with the Vichy government] and Eugene Deloncle [founder of the Caougle and the MSR – a collaborationist party] were working together. In 1941, they had a public argument after which Jeantet subsequently resigned from the MSR and becomes anti-German. Detective Chenevier discovered that in reality these two men had many opportunities to be in contact and were in contact to collaborate on organizing the murder, paying for it, and afterwards shielding the murderers. So the “public” argument may in fact have been a staged, strategic performance while, in fact, they actually kept in touch and, we contend, plotted Dormoy’s assassination.

The involvement of François Mitterand, who was to become President of France in 1981, was previously revealed. A biography by Pierre Péan [Une jeunesse francaise: François Miterrand, published in 1994] brought this to public attention before Mitterand passed away. There were a couple of other men at a high level, but they were shielded by Mitterand.

TOM: What else?

GAYLE: The research makes it clear that the traditional interpretation of Dormoy’s assassination where Annie Mouraille put the bomb under his mattress was debunked. They weren’t lovers as someone previously suggested. Instead, the bomb had to be smuggled into the hotel and Dormoy’s room with a bouquet and a suitcase.

TOM: I was surprised by the corporations who were in support of the Cagoule like Renault, Michelin and L’Oréal, as well as a number of prominent individuals. Why would companies, let alone individuals, want to support the subversion of the existing government, the Third Republic?

GAYLE: Individuals were seeking power and financial gain.

A lot of these companies firmly believed that the Bolsheviks were potentially more dangerous than the Nazis. The Nazis, despite their national-socialism, believed in capitalism and keeping the business elite in power as long as they kow-towed to the military. Bolsheviks wanted to destroy capitalism. The other argument they made was that they could create jobs for people. Even with an authoritarian government. Finally, they also later claimed that they didn’t have a choice. France was occupied and the Germans were going to kill a lot of people. There were a variety of different rationales. It varied among businessmen between opportunity and ideology.

These companies remain important in France and they don’t want their reputations tarnished. So while it is well known at this point that certain firms like Renault and Michelin were supporters of the Cagoule, many people in France after the war – and since – have been willing to turn the page because these firms are so important to the French economy.

TOM: What was the role of the Catholic Church for better or for worse?

GAYLE: The Catholic Church was definitely to the right, but it was more traditional right, more in line with the Mitch McConnell right, not the QAnon extreme right. There were many social issues where clergy and lower level priests sympathized with the economic inequalities.

The extreme capitalism of the right is contrary to the philosophy of the Catholic Church which is also stridently anti-communist. And for the most part the Catholic Church is not in favor of authoritarianism. They wanted a republican government that would give more privileges to the Church than since the late 19th century.

In the 19th century the Catholic Church gained back a lot of what was lost during the French Revolution. When World War II broke out, many of the Church leaders were Pétainists [supporters of Maréchal Philippe Pétain], but they didn’t see him address the economic issues or the persecution of Jews, so many went to the Resistance.

Those who were first affiliated with the Vichy government but later jumped to the French Resistance when it seemed politically advantageous to do so, became known as Vichysto-Résistants. They were not happy with the Popular Front [Leon Blum’s party] or the status quo of the 1930s. And they weren’t going to take action against the Third Republic. They gave Pétain a chance, but his eventual collaboration with the Germans became a negative.

TOM: Do you believe France could have become an authoritarian state? If so, would the French have tolerated that?

GAYLE: It’s hard to say because there are a number of factors. Bottom line, probably not. Had the war not happened and events continued, there would have been more violence, but not necessarily a civil war.

It’s unlikely the Cagoule would have won. Despite the fact they were able to infiltrate the military, they (like the far right extremists in the US today) were still very much a minority. So it’s unlikely France would have had a civil war like Spain installing Franco because the French right lacked a military leader, even Pétain, willing or able to raise an army to try to overthrow the Third Republic. Instead, Pétain let the Germans defeat the French military and then used the ensuing crisis to gain power.

It also would have depended upon where the economy was headed and social pressures.

At that time, the West is in a Cold War with Stalin before World War II even breaks out. In France the Communist party is active and organized and being funded and directed by Stalin from Moscow. In the absence of World War II, there is increasing interference from Moscow that could have led to more violence. But again there wasn’t a military leader in France to take on the mantle. Pétain was old and had to contend with other generals who were not fans of overthrowing the French Third Republic.

TOM: I would imagine that “clues” led you from one place to another. How did you know where to look?

GAYLE: It was more of a pilgrimage. Marx Dormoy was killed in Montélimar and so there was some information in their archives. However, most of his files were sent to the Archives of Paris following World War II once the murder investigation was reopened. Our richest source, particularly for the Cagoule, was the Archives de Paris.

We also went to Moulins for the Archives départementales de l’Allier because Jeanne Dormoy [sister of Marx Dormoy] and her brother’s hometown was Montluçon, in the Allier. The archives of Jeanne Dormoy were thus sent here.

We searched the archives in Marseille because most of the Cagoule came from Marseille. Five of the six assassins of Dormoy were from Marseille. But the leaders of the Cagoule were mostly Parisian even though there was an important branch of the Cagoule in Marseille, which has been, and still is, a traditional bastion of French right wing politicians.

In addition, there was a famous policeman, Etienne Mercuri, whose investigation was based in Marseilles. We had a suspicion there might be new information there from his investigation and there was.

Part of the job of a historian is to learn how to track things down. You need to learn how things work in the country, where information is stored and organized. Experience and persistence are the most important things.

A lot of work is done online. You used to have to physically go, find the documents, then do your review. Now there are printed files online of the archives content.

In general, the more experience you have knowing certain kinds of documents are going to be found under certain call numbers, the better your success. For example, judicial documents are different from notarial, municipal and church documents and all are filed differently.

Students doing their first dissertation will often be guided by their director. Pierre Jeanen in Paris told me that I needed to go to Rouen for what I was working on for my own dissertation. He also directed me to Toulouse for other documents. But sometimes there is serendipity that comes with persistence.

TOM: Did you have grant support because the costs must also have been enormous over the ten-year period?

GAYLE: We did receive some grant money from our institutions. But we had to squeeze time from our schedules to make it work. I’d teach the whole school year, even over the Christmas break, and Spring term too. I never took vacation. It was a labor of love and we dipped into our own funds. We were very dedicated to the project.

TOM: What about securing permission to view classified documents, the process of obtaining derogations? How does that work?

GAYLE: The procedure is to request permission from the Minister of the Interior bycompleting a form and indicating what you want to see, your qualifications, what you intend to do, and justification for why you should be able to see the documents.

In 2006 & 2012, the French government passed laws to open the archives that were protecting the privacy of families involved for several generations. By law, sensitive documents may be protected for 128 years. Others, for 75 years. Laetitia’s documents [Murder in the Metro] were sealed only until 2008 given the change in the law. The documents related to Marx Dormoy are still sealed in Paris in part because they are mixed in with the documents surrounding the trial of Maréchal Pétain, which is still very politically sensitive in France.

For the period of World War II and post-World War II, the archives were given more latitude. But there were also regional differences. Some documents have been unsealed up to 1955. But there is some controversy around Cold War material being declassified. So they have been shut back down again because descendants (for 2-3 generations) have the right to petition to say the information is sensitive to their family and shouldn’t be available to the public. An example would be the papers regarding the involvement of the Renault company. The corporation and the family don’t want them to be made available yet.

In Marseille they didn’t care if we didn’t have a derogation. They just brought out the boxes we requested. We were also allowed to photograph. In fact, most of the book’s photos came from these files. This was quite contrary from Paris which demanded the derogation and sometimes denied certain documents even existed. Whoever runs the Archives de Paris is far more compulsive and rules-oriented.

In reality, these things are a judgement call on the part of the head of the archives. In the case of Marseille, most of the documents related to Marx Dormoy had to do with the investigation of the actual assassins, carried out by Etienne Mercuri in Marseille. The archivist there deemed them less politically sensitive and thus allowed them to be accessed, and photographed without a derogation. Annette and I still had to get the permission of the archives to put them in the book.

There is a militant Communist historian, Annie LaCroix-Riz, who is a diligent researcher. She has written maybe a half a dozen books that have essentially exposed the Renault story with half the book being footnotes. It will be harder to keep this information under wraps given her multiple sources of information.

After 1960 and the war in Algeria, information regarding Charles de Gaulle and others is still sensitive. But the 1945-1960 era will be harder to keep secret. Still, there are certain archivists who will not make it easy. Their motivation is that they are trying to protect Francois Mitterand. I suspect it sometimes depends upon their own political leanings. They don’t want foreigners coming in and photographing this period of French history. It’s too soon.

It was particularly challenging in the Archives of Paris where information was scattered between various files, including Pétain’s eventual post-World War II trial. I discovered sensitive documents having to do with Franco/Anglo-American spy networks. There were huge amounts of money in the hands of both the US and French governments to create spy networks. So our research included examining documents from the pre-war, wartime and post-war periods.

TOM: You mentioned that Pierre Laval was first head of Pétain’s cabinet then removed because of their disagreement regarding collaboration with Germany. Laval later came back to the cabinet. Was it the Germans who forced that?

GAYLE: Yes. Laval was replaced by Admiral Darlan. Darlan was determined to use the Riom trials as leverage for the Germans. [The Riom trials were held for charges against the leaders of the Third Republic].

Maréchal Pétain was only concerned about protecting his reputation. The problem with Pierre Laval is that he was pushing a closer collaboration with the Germans. But the French didn’t want this. Collaboration wasn’t all the Germans wanted. The Germans wanted to keep France tightly controlled because they needed the resources of French agriculture and industry to sustain the German war effort. One French “resistance” strategy became to do what one had to, but moving slowly, often playing a wait-and-see game to see how events unfolded.

The staged event where Maréchal Pétain is shaking hands with Adolf Hitler in October 1940 created very bad publicity. The French people were shocked because they felt a certain distance was going to be kept from the Nazi government. This instead spoke to open collaboration.

Pétain subsequently had increased difficulty exercising control. He therefore needed a minister to squeeze concessions out of the Germans for limited collaboration. Laval portrayed himself as a negotiator so he was thus engaged. Finding his popularity slipping, and realizing that Laval is not getting very far, Pétain soon scrapped Laval and brought in Admiral Darlan.

What Pétain didn’t understand is that the Germans weren’t interested in anything other than having France as a subordinate, occupied by Germany. Hitler otherwise had no intention of allowing France any power or independence because of his vengeance for what happened in World War I. France would never be a partner, let alone an ally. The Nazi government had no intention permitting France ever to be an equal partner with Germany in the “New European Order” even if the French adopted Nazi ideology.

By 1942, it’s clear that the war isn’t going well for the Germans. And the German demands on the French are increasing. Once the Allies invade the Mediterranean, things are going further south for the Germans. Darlan isn’t accomplishing anything, so Laval is brought back in to negotiate a more favorable outcome. But that doesn’t work because the Vichy government has been reduced to a figurehead government. This happens in November 1942, when the Germans invade the Vichy Zone after the Allies have invaded North Africa.

TOM: You write that Admiral Darlan goes off to North Africa. He is soon thereafter assassinated. What happened? Who was behind the assassination in Algeria?

GAYLE: Darlan was in North Africa in December 1943, to visit his son who was ill aboard one of the ships on the French fleet holed up there. By then Mussolini had been toppled and the Allies were in control of much of Italy and North Africa. They wanted to negotiate with Darlan to get him to surrender the French fleet to Allied control. He agrees, but is assassinated by someone who is disgruntled because he has switched sides. The French are divided and there are people in the military who are collaborationist. The Allies gained control of the fleet anyway, and begin negotiating with General Henri Giraud (mostly because Roosevelt disliked and distrusted Charles de Gaulle).

TOM: You also wrote that Detective Chènevièr & Gabriel Jeantet were “broken” as a result of their incarceration in German camps. What happened to them?

GAYLE: Jeantet got typhoid fever which was fairly common in the camps. He returned from Germany, probably with pneumonia, was admitted to the hospital, cared for and then placed under arrest. He was never indicted for Dormoy’s murder because the French government didn’t feel they had enough evidence to pursue him (the official line). He was sentenced to 7-10 years hard labor and Indignité National, which prohibited him from ever having a political postion. Later he was amnestied. He then picked up his career, wrote books favoring Pétain, and became a television journalist. When he was diagnosed with cancer, he commited suicide in 1978.

Chenevier returned from the war sick. Because he worked as a police commissioner with Vichy, he is accused of collaborating with the Germans and handing over suspects. The investigational result was inconclusive. He fought it for a couple of years and was ultimately exonerated. Because his role was questioned during the re-examination of the Dormoy murder, Chenevier was allowed to testify as a witness, but he could not take an active part in the investigation when the case was reopened. He went back to police work and started a detective agency. It became the largest in France and is still run by his son and grandson.

There was a German spy expelled following an investigation by Chenevier. When Chenevier was arrested, it is this same man, now in the German Gestapo, who tortured him to get answers. Chenevier’s illnesses resulted from his time in the camp, but not from the torture. In the camps, there was little or no medical treatment. They were badly fed, cold etc. Many returned with their health broken. George Kubler, the Commissioner in charge of the Dormoy murder based in Lyon, died in the camp.

TOM: Who amongst the Cagoule eventually took the hit for their treasonous activities? Why did the others get away?

GAYLE: It depended upon several things.

Joseph Darnand [who headed the Cagoule in Nice] was caught in Italy, returned to France and promptly executed for treason in October 1945.

Jean Filliol [the notorious Cagoule hit man] fought in the final days against the Germans but escaped to Spain.

It basically came to who got caught. Those who went to Spain did the best because Franco wouldn’t extradite them.

Pierre Laval and others tried to hide out in Switzerland but were sent back. Laval was executed pretty quickly in October of 1945 after being sent back to France, where he was immediately tried.

Those who were in Italy were at the mercy of the Americans who came to control the country after the fall of Mussolini. If you were regarded as potentially valuable, despite your history, you were provided opportunity. Otherwise you’d get sent back to France to suffer whatever consequences. No one want to be in the hands of the Soviets.

Gabriel Jeantet was labeled a Vichysto-Résistant. He faced trial for his Cagoule activites and given a sentence, but most of that was abandoned by amnesty laws.

By 1958 most were out of jail.

It largely depended upon what that they did during the war. Lower level Cagoulards were never followed up on. One Cagoulard, Jaqcues Corézze, came to the US to head a branch of L’Oréal.

Francois Miterrand was the most notorious in that he had contact with a lot of these Cagoulards and protected them. But as a Vichysto-Résistant he was able to salvage his reputation, switch political allegiances, and enjoy a successful career as a socialist leader.

TOM: Many of the Cagoule furthered their political careers within the French government hiding their past, perhaps the most public example being Francois Mitterand as you’ve just noted. Was their background at some point common knowledge and simply swept under the carpet? If so, why?

GAYLE: It depends upon the individuals. Everybody who was in the government after the war had a past. During the war, there actually weren’t that many in the Resistance. By the end of the war, the numbers of resistors had, of course, swelled enormously. The numbers who claimed to have joined the Resistance was even higher. But during the first two years of the war, there weren’t that many who dared join the Resistance. Most French people simply hoped Pétain would salvage some sort of French independence.

By the beginning of 1943, three things had changed:

- The Germans have invaded the Vichy Zone, dashing any hope that Pétain could preserve French autonomy.

- The tide of the war had turned with Allied victories in North Africa.

- German demands on the French economy began to bite more deeply, especially their demands for French labor in German factories. A lot of young men began to join the Resistance in part to avoid being sent to labor in Germany.

Following the war, de Gaulle’s desire was to unify and reconcile France. Some went to great lengths to cover up their past. They didn’t want the embarrassment of being identified with the wrong side or perceived as traitors to France. Some of these were members of the Cagoule who ended up in the post-war government. There was therefore a deliberate amnesia. People knew who they were, and it would be whispered about in corridors. But, yes, a lot was swept under the carpet in order to move forward.

Francois Mitterand’s involvement was commonly known even up to 1985. But it was always whispered about. It was a case of “We don’t want to go there.”

Gabriel Jeantet, who played a leading role in the Cagoulard and later the Vichy government, was condemned but most of his sentence lifted. As mentioned, he was given Indignité Nationale, which doesn’t exist in the US. So rather than politics, he instead went into journalism. He claimed that he was a resister during World War II. And no one talked about France in the 1930s when France was most divided.

Eugene Deloncle by this time was dead, having been assassinated in January 1944, probably by the Gestapo, who realized he was turning against them.

Except for the most egregious collaborators, they came to believe that most everyone was a secret resister, especially Michelin and Renault which, even today, are too important to industrial France even though they supported the Cagoule before the war.

TOM: There are parallels between France in the 1930s and 1940s and the US today – fighting for its soul. What is your take on that?

GAYLE: Annette and I are currently working on an editorial on this topic. There are several areas where there are parallels. One is the use of fake news. Marx Dormoy tore the veil off the Cagoule in late 1937 and 1938 when the existence of the Cagoule was denied. Turning the tables the Cagoulard, via friends in the press, said whoever the culprits were, they were bumbling idiots and on the Left, not the Right. They used the Phantome Marx (Marx’s Fantasy) with the cartoons of Dormoy running around looking for nonexistent Cagoule. The word Cagoule was coined by a right-wing journalist (DeBorgia) to make fun of the Cagoule, as hooded figures like the American KKK.

The strategy was to use the media to create a parallel reality so the facts are ignored. This is important because even historians were taken in by this. They seemed to have bought the fake news and didn’t believe the so-called Cagoulard activities posed much of a danger. It made it therefore harder for Blum’s government to make the case that they needed to take this seriously.

More and more scholars are in tune today with the danger of the Extreme Right in society. They don’t have to take power. Their aim then was destabilization and confusion to make the country appear to be ungovernable undermining the Popular Front. If successful, the Right would ultimately come to power and the Third Republic would be overthrown.

In the US, the extreme right is calling the left extremists. But there isn’t an organized party threatening values. Even Bernie Sanders is considered socialist and left of center, but not in the extreme. Trump’s supporters are casting blame on ANTIFA in the same manner. The underestimation of domestic terrorists is coming from the Right.

In the Fall of 2019, Annette and I were invited to a conference on Right-Wing Terrorism in Erlangen, Germany. Much of the discussion was about this danger. When the conference ended, it was discovered that someone at the conference had taped a large knife under one of the tables. Someone in attendance was an infiltrator. About 50 people were present including researchers from Hungary, Romania, and a few from France. The laptop of one of the organizers was also found to be deliberately destroyed. They don’t know who did it, but it had to be one of the scholars attending the conference. I got the sense there were sympathizers present. You don’t know until you know.

The use of violence to create confusion and intimidation, twisting reality that are persuasive is not unique to Trump.

TOM: Where is this headed for the US? What is your biggest fear?

GAYLE: The good news for the US is that the center and our institutions have held. We’ve managed the transition of power and for the moment, things are stabilized. But we can expect more incidences of violence and provocation trying to bring the Left into conflict. It will depend upon President Biden. The best way to peel support away from the extreme right backers is to show them that they aren’t forgotten and neglected. Show them that government can work. Show them Biden’s policies will benefit them.

The racial tensions are multigenerational. The culture wars, the defenders of the status quo [white supremacists] are becoming more violent because they are becoming the minority. In another generation, these tensions will be reduced because of blending and mixing. It seems to be the only solution. Familiarity in the workplace alone doesn’t remove the tension because people go home to their isolated lives. Once socialization increases, the tension will ease.

The next few decades are going to be rough. Between the impacts of climate change, the COVID recession, the economic challenges of the rise of China, and the competition for markets, there will be fierce competition for resources, government aid and jobs. It’s going to be difficult for the US and in a lot of other countries when people feel like they are losing ground and heading down the socio-economic scale. Unless we can find a way to expand the economy, expand jobs, and expand resources in the US and across the world, there will be more tumult.

Climate change will add to the mix because it will be costly to address the problems that climate change creates. Resources will be stretched thin creating competition and conflict. In the longer term, the US will manage to find solutions because of its ingenuity and creativity. Plus the younger generation has a different mindset open to racial diversity and lifestyle changes.

TOM: You have written a fascinating book rich in detail that has revealed so much and gives a brilliant analysis of France in this time period. What’s next?

GAYLE: Our next book will also be on the Cagoule. We want to look at the end of the war, the Cold War period and what happens to these Cagoulards. We may also write a narrative synthesis of the Cagoule.

TOM: Well, thank you for your time. It has been fascinating to learn about this period of history in France via your book and this discussion. While we tend to romanticize France, it is a book like this that lays it bare that there is often a dark side. I have found that history repeatedly shows humanity can be very unkind. I hope your diligent research will expose the negative aspects of current events in a powerful way so that we who live today can work to a better outcome. All the best in your continued work!

Thanks so much Tom for this excellent synopsis of the book and our conversations!

Avec plaisir, chère amie! It was indeed a pleasure to read, to discuss and contemplate. History always has something to teach us. And the parallels with these events from the mid-20th century to politics today are astounding.

History often rhymes. Great research. Terrific interview. Well done!

Always learning from the past with its parallels to the present. Thanks for sharing this fascinating chapter in French history. Congrats to your two amazing author friends, Tom! Kristin

Quite a project- so much to digest and integrate.